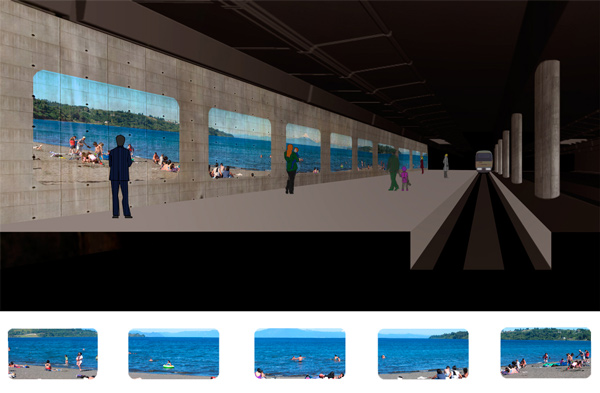

Through a projection device that evokes the perceptual experience from the train, the viewers will be invited to lose themselves in images during their wait. The projections acting as windows, the station itself becomes a train that loses its spatial and temporal rails, itinerant across the earth.

From the salt flats of Uyuni to the roads of Saigon, from the plains of Siberia to those of Patagonia, from the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge to the Orinoco River to central Montreal to the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro to Johannesburg’s Soweto to a Kensington street to Oaxaca market to Plaza Mayor to the Sicilian coast to Jalpur to Alexandria to Fortune Bay to Kualalampur to Ulan Bator to Den Haag to Reykjavik to Marienville to Tallinn to Corbridge to Buenaventura to Faisalabad to Muscat to Adana to Kinshasa to Xiangkhoang to Arrecife to Krakow to Pusan*… the Malmö C station will travel the world. Itineracy, like a lost river, flows continually into an underground passage. It is said that one never steps in the same river twice; comparably, the Itineracy installation is elaborated in such a way that it is unlikely that a viewer on a fixed schedule will see the same image time and again.

In terms of tempo, Itineracy is conceived as a release for the individual viewer. The recorded images are slowed down, in contrast with the speed of everyday urban life, in order to ease the experiential flow of time.

In symbolic terms, this artwork highlights the importance of the Central Station as a node; in its primary sense, as a crucial railway link, but also metaphorically as a connection between the city and the entire world.

* the list is neither contractual nor exhaustive

The

concept of the installation Itineracy emerged from a series of

reflections concerning the historical relationship between the railway

systems and the notions of simultaneity and universality as well as the

implications of these notions nowadays.

The concept of “Universal

Time” is a recent one. Before the nineteenth century, when a trip from

one country to another took days, and from one continent to another,

months, there was little need to coordinate the time between different

places. The introduction of standard time, in the early nineteenth

century, was closely related to the development of the railway system.

Just as the standardisation of time begets the idea of synchronisation,

the establishment of a universal time begets that of simultaneity.

Two hundred years later, we assume blindly that the entire globe is

permanently living a singular moment, a universal present. What is

more, we know that in economical as much as in ecological terms we are

tied to people situated in distant everyday realities and landscapes.

This condition is visually addressed by Itineracy.

Since our link to distant people is far from a simple given, particular

attention is conferred in the filming process to the subject of

borders, in terms of human, physical and political geography.

Subsequently, even if those borders remain present in the captured

landscapes, they are metaphorically abolished by the installation

structure, where new continuities and contiguities emerge constantly.

The screens being designed to suggest windows might affect the

interpretation of Itineracy, given the paradoxical nature of windows

themselves as closed openings. Following this logic, this installation

can be seen as a transparent opening which protects viewers from the

outside world as much as it projects them into it.

This piece is deliberately set to be multi-layered. Open to the public,

it intends to raise questions rather than to give answers. Hopefully it

will encourage unexpected interpretations. Ideally it shall be

captivating enough that viewers will ‘loose their train of thought’ or

even be tempted to miss their actual train.

This

installation is related to western and eastern landscape traditions:

panoramas and rolled screens. Panoramic monumental imagery reached its

peak during the nineteenth century, when commercial panoramas were a

popular entertainment industry in several European and North American

cities. Special buildings were constructed to hold enormous circular

paintings that, with their heightened illusion, attracted the crowds.

Less static, traditional Chinese rolled screens entail both a manual

and visual act of unrolling. Amongst other subjects, descriptive and

narrative landscapes where remarkably executed for centuries in that type of scroll.

Itineracy

can be partially understood as an unrolled panorama in motion.

Comparably to panorama, it proposes a partial immersion. Comparably to

a scroll, it constitutes a device to record space. Composition in Itineracy

acquires an additional aspect, that of time, which becomes as a result

intrinsically tied to the editing process. Analogously, the editing

happens to be in every moment transversal, aware of the spatial

dimension.

The challenge of representing a new type of landscape, a ‘universal and

simultaneous’ one, confronts us to supplementary questions. Where to

and where from? or even, Why moving from here to there?-when one is

already everywhere. As a limited answer, Itineracy, unlike standard

films, does not have a beginning or an end. The final editing is

generative, explicitly a video data base permanently accessed and

displaying the film according to an underlying program. In order to

control the result to some extent but still give a chance to the

unattended, this program combines the pre-recorded sequences in a

partially ordered and partially random manner. This configuration

confers to Itineracy the possibility of permanent mutation and change.

Idea- first drafts

Project- sketches

Tests in situ / Photos M.Diaz

Simulations

Downlad bigger versions: Left / Right

For more information write to